The night I was hit by a truck earlier this month while crossing the street is blurry in places, with some parts missing entirely. I think of the first 48 hours afterward in two distinct phases: the initial hours of confusion, memory loss, and non-linearity; and the remainder marked by pain, overwhelm, regret, and the slow, devastating realization of what had happened.

The day and night of the accident had been completely ordinary. Ordinary, until a second before impact, when I turned my head expecting only traffic coming from the right and instead saw the truck barreling toward me from the left, traveling on the wrong side of the road. Everything after that is blank for maybe half an hour, followed by other gaps and hazy fragments during the three or four hours I spent in the hospital.

I don’t remember anything from the moment just before I was hit until the sensation of being lifted into the ambulance. My eyes were closed, but I had regained consciousness. I remember hearing several voices speaking Burmese and then the feeling of being raised on a stretcher off the ground. I cried in the ambulance, unbearably carsick and dizzy.

I couldn’t clearly see anyone, but I understood instinctively there were good, safe people around me, helping. The voices were tense, overlapping. One of them, I clocked right away: my husband. I could recall our nearly 19 years together, but for maybe an hour I couldn’t remember his name—only that it had either five or six letters. I kept slowly circling around the shape of the name, puzzling over it and getting nowhere. I was stupefied that I couldn’t pin it down. I didn’t know what that meant.

After we reached the hospital and the wave of carsickness finally lifted, I remember flashes from that evening—disconnected moments with no clear sequence. It feels like most of that time I was either heavily medicated or drifting somewhere between sleep and consciousness.

For example, I remember a brief surge of panic when I became aware of a stabilization collar around my neck and felt it was suffocating me. My chest felt crushed and I struggled to take a deep breath. I grasped at my throat trying to tear it off, before someone—whose face I couldn’t see—stopped me. I heard them tsking or gently hushing me as they readjusted the collar just enough to ease the pressure, and I started to calm. I don’t know if that happened in the ambulance or once we were inside the hospital.

I also remember coming to at one moment and realizing I was in a room and feeling suddenly overheated. All I could see was the part of the ceiling directly above my eyes.

In another moment, I recall the embassy doctor simultaneously pressing ice packs to my temple and forehead, her voice quiet and soothing. I could feel her hands, but I couldn’t really see her. The coldness felt sharp and wonderful. At the time, I thought the heat was from lack of air conditioning and that she was trying to keep me cool; only later did I grasp I had bilateral concussions and a swelling on my forehead the size of a tennis ball.

While awake, I kept asking my husband again and again what had happened. I could vaguely see him standing by the bed railing to my left, but the light was too bright and I couldn’t focus on anything, so I mostly kept my eyes closed.

At times, I could hear myself repeating the same questions like a broken record. What happened? How did that happen? But what exactly happened? I couldn’t reconcile my last clear memories with what I was being told. The truck that I saw so close to hitting me actually had? How did everyone know that and I didn’t? I’m the one who saw it! What did I miss? The disbelief and out-of-body feeling that this couldn’t be happening to me outweighed everything—yet it clashed with the truth, and with the anxiety and fear I could hear in my husband’s voice.

The image of the truck bouncing menacingly played over and over in my head on a loop, coming closer and closer. So that already happened? I thought. This wasn’t, couldn’t even be real. I would wake up. But it must be real; I felt like I had been hit by a truck.

I agonized over the million small things that had been perfectly timed to result in this outcome, and imagined some of them changing. If I could go back and change something. Leave sooner. Leave later. Go somewhere else. I imagined I would blink, and we would suddenly be sitting in a restaurant as we’d intended, having caught our Grab and arrived without incident. No accident, no injuries, no hospital — blissfully unaware of the fate I’d almost met.

Waves of pain kept washing over me and anchored me in the terrible now. My husband’s name came to me in a rush and I said it out loud. Our American medical officer appeared at one point next to V and I felt relief to see him. I had the comforting impression he’d been there coordinating things for a long time already and I just hadn’t known.

I heard people talking about me and I was trying to follow along with the discussion, but I couldn’t. The medical officer asked me to move one foot, and then the other, and I did. He seemed pleased. Then I realized whether I could move my legs had been in question and I felt a cold fear in the pit of my stomach. I wondered if my 2021 spinal fusion could have been damaged.

At some point it also dawned on me that I was still the duty officer, and I asked my husband to call my boss to let him know I’d been hit by a truck. Evidently, I asked him at least half a dozen times. I suspected I probably sounded like an inebriated person surrounded by sober people—the thoughts were forming clearly in my mind, but they weren’t coming out of my mouth the same way. The idea of the duty phone ringing and me not answering filled me with dread. It felt crucial that someone tell my boss I was no longer plugged into that unspoken consular-manager vigilance.

I remember people pulling the curtain around the bed and seeing some men standing on the other side of the room disappear from view. Women helped to remove my jeans, tank top, and bra. Even though they explained I needed to change into a gown for a CT scan and I tried to cooperate from my laying-down position, I still broke into loud sobs from the pain of trying to lift my arms and trying to wiggle out of my jeans. I also kept trying to arch my head up and see if the curtain was all the way closed. I resisted my rings, bracelet, and earrings being removed, and although V showed them to me in a bag I asked about them repeatedly. It never occurred to me to ask where my purse was though, which in retrospect astonishes me. I don’t remember any actual scans so I must have passed out again.

Sometime later I saw our regional security officer, looking intently across the room at something or someone I couldn’t see. The familiar people around me had started to come into sharper focus. Slowly, I became a little more lucid. I remember the medical officer telling me we were leaving the hospital and heading to the embassy health unit, where I would sleep. I struggled to follow what he was saying. I had the distinct impression we were done with whatever we were doing and it was time to go.

I felt strongly that I was in good hands, and that things would start making more sense soon. I had a vague awareness that hours had passed, yet no memory of most of it. I wasn’t wearing a watch before the accident, and didn’t know what time it was. If I was there for four hours, I can only recall maybe 30 minutes in total, and not sequentially.

It was around this point that my memory becomes more continuous again. I remember doing a partial self-assessment and zoned in with surprise on all the wounds on my arms, hands, and fingers for the first time. I noticed a wound an inch from my tattoo, but mercifully no damage to my tattoo itself. I was unable to assess what was happening with my legs or feet, but my chest, back, and hips hurt like hell.

The next thing I remember is being wheeled on a stretcher down a hallway and out what seemed like a back door. I couldn’t see my husband. As we exited the hospital, I looked around and saw the night sky. Cars were parked nearby and people moved around in the dark, but the surroundings were unfamiliar to me. A line of hospital staff had gathered outside the doorway, all watching me being lifted back into the ambulance. I lifted my hands in a prayer gesture as a silent sign of thanks to a woman who met my eyes; she raised her hands in return.

In the back of the ambulance, a local guard sat with me, not speaking but watching with kind, alert concern. I tried to focus on her face, but my eyes kept closing. I could feel her looking at me. I wanted to say something about the stray cats she and I often pet together on the embassy grounds, but no words would come out.

I think my husband might have said something to me from the front of the ambulance to let me know he was there. I noticed a car through the back window following closely behind us with its hazard lights on. One of ours, I thought vaguely. Seemingly several minutes later, I glimpsed the main entrance of the embassy sideways out the window. I realized with a start where we were. I remember driving into the embassy compound, and approaching the chancery.

I remember waves of surreality washing over me as I looked at it all from my sideways vantage point. How am I going through the front door of the chancery that I’ve walked through 200 times laid flat on a stretcher? And then suddenly I was watching it go by. Everything was happening too fast, like one of those old reel-to-reel movies where the picture keeps skipping a frame.

As relieved as I was to see the embassy, a strange shame washed over me—irrational but overwhelming. It felt as though I’d somehow done something embarrassing, and this was the humiliating consequence. I couldn’t quite make sense of it, but there was a deep sense of having lost the dignity of all the mornings I’d ever walked through that door in a suit, composed and ready to face the day. Now I was returning broken, carried, helpless.

Layered over that was a profound disbelief, a kind of internal revolt against the reality of what had happened. My mind kept flickering toward the impossible command: undo. Delete. No. This can’t be right. In what version of my life—of any life—could this truly have happened? How could every moment of my life until now been inevitably leading to this hidden moment?

Well, maybe you shouldn’t have jaywalked! a judgmental voice in my head advised. I’m the victim! I mentally shouted back. This happened to me, despite everything I’ve done right! I pictured thousands of people all over the city at that very moment, doing riskier things and getting off scot-free. A flash of anger moved through me.

I remember being wheeled in a wheelchair to the toilet in the health unit, where I used the bathroom for the first time in several hours. I was surprised to see I was wearing two hospital gowns tied together front-to-back. I was even more surprised to notice my makeup looked unusually glamorous and undisturbed. My lipstick and eyeliner looked like I’d put them on moments before, despite the crying and the hours that had elapsed. Other than the blood and debris in my hair and the giant swollen part of my forehead that all looked like a Halloween costume, my makeup appeared virtually undisturbed. How strange. That’s a potential paid partnership with my setting spray! I started to chuckle but my cracked ribs stopped me.

I remember laying on a railed stretcher or table and having something near me, maybe a bell. I realized V and the medical officer would also sleep in the health unit to keep an eye on me. I took the pills I was given and felt the softness of the blanket. I only remember waking up once.

I woke up late, maybe around 9:00 the next morning, and began the painful process of getting into a vehicle to be driven home.

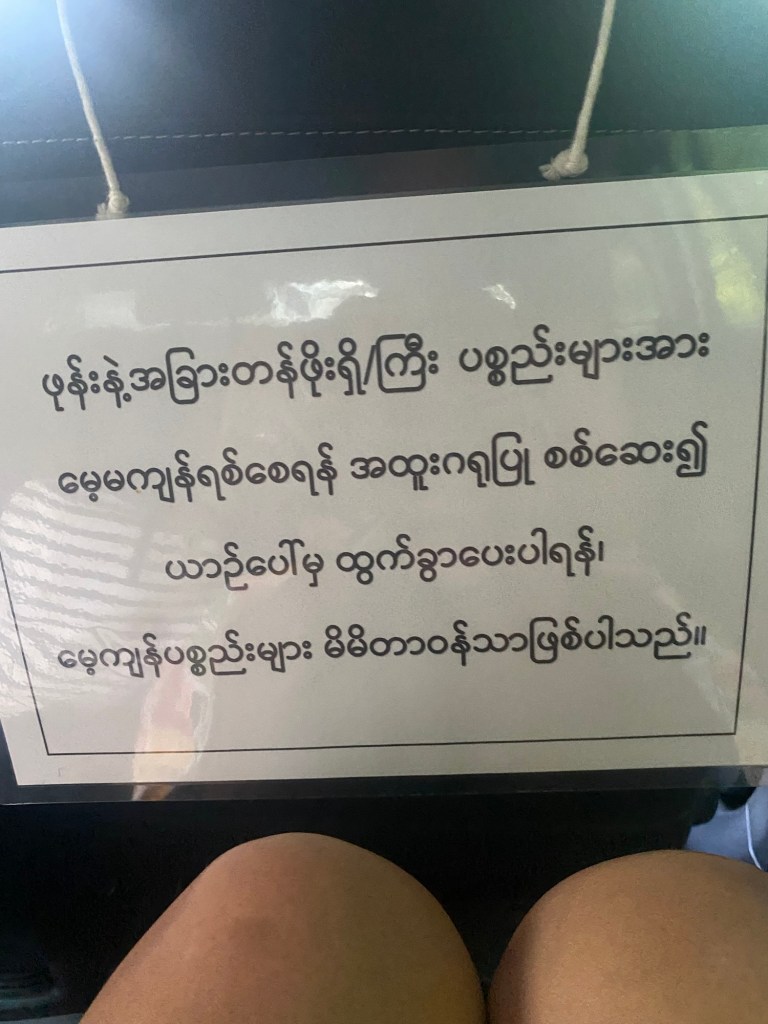

“Please take special care to check and leave the vehicle so that phones and other valuable/large items are not forgotten.

Forgotten items are your own responsibility.”

To be continued…

Geez, you and V can’t catch a break. I’m hoping you’ve used up all your bad luck for the foreseeable future and things move up from here… Sending love and happy Thanksgiving!

LikeLiked by 1 person