If you have ever attended a celebration, speech, or conference in Australia, chances are it began with the speaker or master of ceremonies acknowledging the traditional custodians of the land you were on. That protocol is called an Acknowledgment of Country.

If you are truly lucky, you may have even experienced a Welcome to Country by an Aboriginal elder (sometimes also referred to as an Indigenous Australian). This Aboriginal welcome practice has been going on for thousands of years, long before the first white settlers landed in Australia. It is rooted in the Aboriginal cultural awareness of being in your vs. “another’s country,” how to ask properly for permission to cross into someone’s land, and how to welcome others into your land.

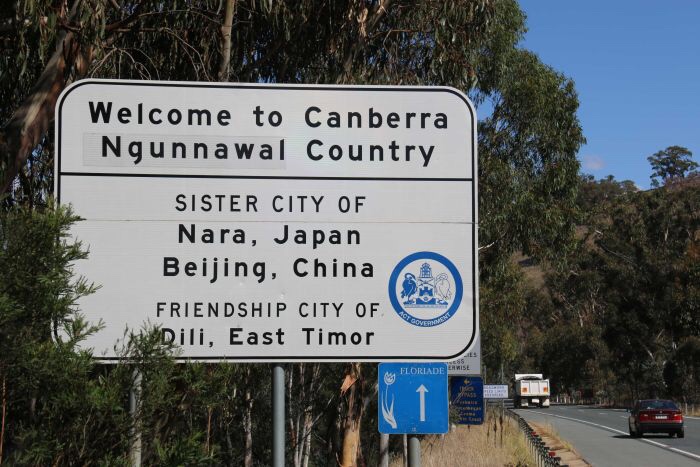

I have been fortunate at many formal diplomatic events to experience such a welcome. Although Welcome to Country addresses are given by indigenous elders, anyone (indigenous or non-indigenous) can give an Acknowledgment of Country. It is a wonderful opportunity to pay respects to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and acknowledge that, in the case of Canberra, you are in Ngunnawal Nation.

Photo Credit: Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC)

Over the last year and eight months that I have been in Australia, the heartfelt intention behind the Acknowledgment of Country ritual first surprised, then delighted, then deeply touched me. I do not remember it from the first time I lived here (2005-2006), but understand that it started happening around the early to mid-1990s, years before even Reconciliation Australia began its important work in 2001. Federal parliament opened its 2010 session with an Acknowledgment of Country, and apparently observing the practice became common.

The Acknowledgment of Country can have several variations, including customization for different areas and the traditional owners as applicable. But it usually sounds something like this:

We wish to acknowledge the traditional custodians of the land we are meeting on, the Ngunnawal people, and honor their leaders, past, present, and emerging. We wish to acknowledge and respect their continuing culture and the contribution they make to the life of this city and this region. We would also like to acknowledge and welcome other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who may be attending today’s event.

The University of Canberra explains the significance in this way:

In the spirit of Reconciliation as a key underpinning value, the University of Canberra (UC) supports and encourages staff and students in promoting Reconciliation. The University acknowledges and implements cultural protocols as ethical principles that guide our conduct, including performing a Welcome to Country or Acknowledgement of Country at the commencement of events prior to all other matters.

Australian Capital Territory Police (like many other national, state, and territory branches of government, along with universities and numerous other organizations) have on their website their own customized Acknowledgement of Country, which says:

ACT Policing acknowledges Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as First Australians and recognises their culture, history, diversity and their deep connection to the land. We acknowledge that ACT Policing is on the land of the traditional owners and pay respects to Elders past and present.

In order to really understand what Reconciliation means to Australia, you have to know something about the Stolen Generations. My first exposure to the Stolen Generations was in 2005, before I moved to Australia for the first time.

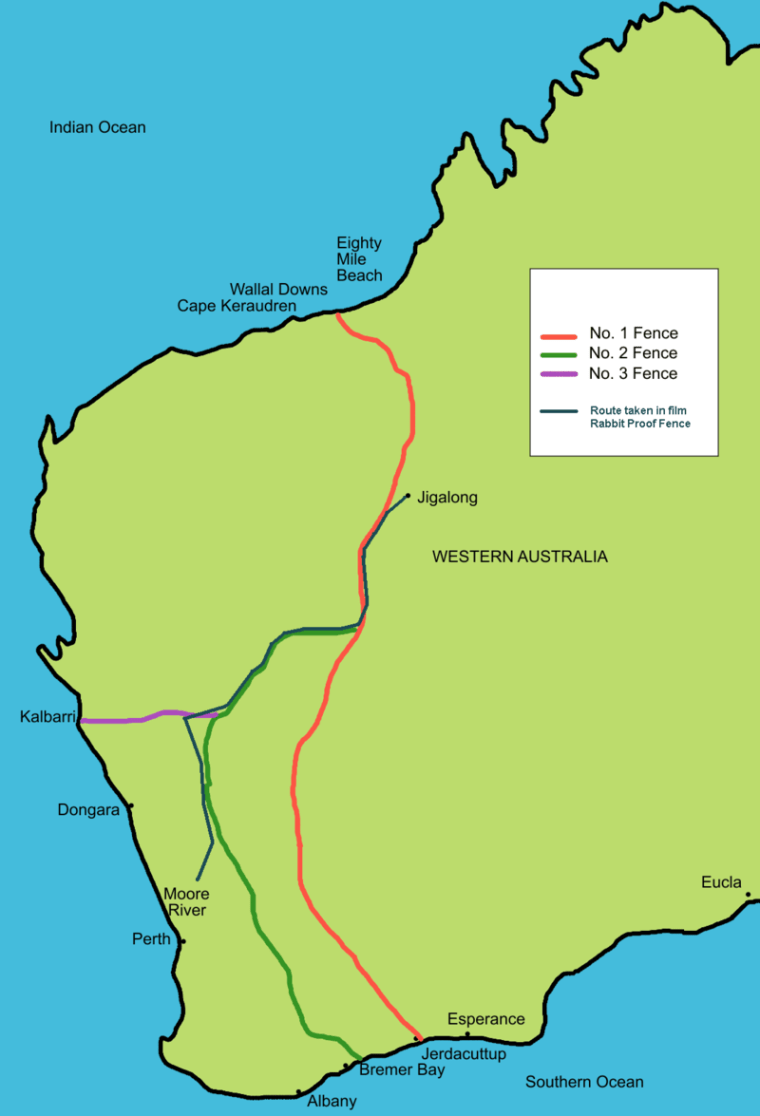

On my mom’s recommendation, I watched a 2002 film called Rabbit-Proof Fence. It is based on a true story about the journey of three little Aboriginal girls (two sisters and their cousin) the Australian government removed from their families in Jigalong and placed in the Moore River Native Resettlement Camp in 1931. To escape the camp and return home, they walked for more than nine weeks along 1,500 miles (2,400 km) of fencing. The fencing, built 25 years earlier to keep out non-native rabbit pests (introduced to Australia in the 1780s) was the girls’ guide as they made their way towards home.

Source: Wikipedia

But their story does not end there: I highly, highly recommend this film if you have not seen it. Between the early 1900s and as late as 1970, the Australian government removed mixed-race Aboriginals they termed as “half-castes” (now an archaic, offensive term) from their homes to state institutions.

The Assimilation and child removal policies sought to integrate those deemed “suitable” into white society, where their names were changed and cultures of origin discouraged. They were forced to assimilate, and encouraged to marry whites until after four generations, they were themselves considered white. In a cruel twist, much of white society did not accept these mixed-race Australians, no matter how white they appeared or “acted.”

No definitive numbers exist for how many people were part of the Stolen Generations. Many Aboriginal parents whose children were removed never saw them again. I met one in Melbourne in 2018 who I will never forget. She is a poet and an opera singer, and spoke publicly of being removed from her family as a child in the late 1960s. The shame at being forced to deny her culture, the abuse she suffered in state institutions, the trauma she experienced when reunited with her elderly mother and aunt as an adult – was all simply heartbreaking. Tears flowed freely in the audience, including my own, believe me.

This is not the familiar Australia that I know and love, in a similar way that the America I know and love should have never allowed the barbary of slavery. And yet it did, among many other injustices, and to deny it would be wrong and smacks of privilege.

Part of being truly remorseful for a wrong done is saying it, openly, publicly, and out loud. This is a big part of Reconciliation and building a more fair and cohesive society. An Australian government inquiry commenced in 1995 and completed in 1997 estimated that up to 33% of Aboriginal children had been subject to child removal policies over more than six decades. The report made recommendations, including a formal apology.

In February 2008, then-Prime Minister Kevin Rudd delivered a speech entitled National Apology to the Stolen Generations in federal parliament. The purpose was for parliament to “officially acknowledge the responsibility of their predecessors for the laws, policies, and practices of forcible removal.” (Source: Museum of Western Australia) You can read the transcript of PM Rudd’s statement here.

I make these difficult observations about the past of Australia, a country I love and respect deeply, as an outsider looking in, in order to understand why the Welcome to and Acknowledgment of Country are so special. I know that there is hurt, regret, and pain, and that true reconciliation will be a long road.

The United States certainly has its own complicated history with race relations, issues of social cohesion, and mistreatment of native peoples (or what the Australians would call First Nation peoples). And these issues are still very much present today and we continue to grapple with them.

I find it hard to imagine Congress opening a session with an Acknowledgment of Country, paying heartfelt respects to the traditional owners of present-day Washington, DC. I could be wrong. I hope I am wrong. I would like to see our national discourse include an awareness of Native Americans being traditional owners of our land, not just buried in some piece of legislation or government subsidy, but with some actual humanity and empathy. And perhaps the concept that asking for forgiveness is appropriate?

But I think the Australians’ awareness of what it takes to truly reconcile the people who all love their homeland is still ahead of ours. The Australians have my deepest respect and admiration for admitting past wrongs, and taking something like Acknowledgment of Country – which could easily come across as an insincere ‘tokenism’, and yet at least to me somehow never does – and normalizing it across society. If we have some distance to go, let us take a step. And another.

While my mom was visiting last month, we traveled to Australia’s island state of Tasmania. One evening, while watching the local news, we saw a heartwarming story about a local couple who decided to return half of their 220 hectare (544 acre) land back to the Aboriginal Land Council of Australia, in Tasmania’s first-ever private land return. “This land will relink us all,” the woman said. “It’s already relinking us.”

This phrase was projected onto the Sydney Harbour Bridge on NYE 2018: “Always was, always will be.”

Another great post. I’m like a sponge soaking up everything you write, as if to compensate for lack of interest in my youth. Thanks for sharing your life as a diplomat! Soon you’ll be talking about the myriad of check-offs you and V must do in preparation for your 2020 move.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are too kind! I am happy and humbled that you enjoy the blog.

LikeLike

I love this post! Such an important issue, and one I wasn’t really aware of in Australia. Thanks for educating us 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person