In addition to ending my fourth tour and traveling to the west coast to see family, I did two other important things in Washington, DC in June. I had an opportunity to march in the Capital Pride Parade as a volunteer for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP), and I went to a work-related training on atrocity prevention at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM).

Both the volunteer work and the training provided opportunities to reflect on important signs we may see that things are going wrong – before it’s too late.

I have been volunteering with AFSP for just over two years. I got involved with their work shortly after I learned of the 2021 suicide death of my ex-partner T, who I’d been friends with since 1998.

T’s suicide has continued to have a profound impact on me. My unanswered questions and the inability to contact him have been things I’ve struggled with.

As anyone who has dealt with a suicide loss knows, suicide is not something those left behind can “get over.” I feel that way about grief in general. But losing someone you cared about at their own hand is a particularly cruel and complex kind of grief. The endless questions, regrets, and anger can feel isolating. It can also leave you in a state of conflict with the deceased with no clear resolution.

Many suicide grievers also contend with circumstances around their loved one’s death being especially violent, tragic, or unknown. Some may also have had complicated relationship histories with the deceased. T’s story to me is all of these things and more.

But the worst thing to try and reconcile has been the loss of such a unique and kind person in the world. The loss of our friendship and the knowledge there will be no new conversations or memories with him are things I’ve had to find a way to carry. As a self-proclaimed “non-tattoo person,” I got a memorial tattoo to keep his memory and a reminder about friendship close to me.

The first year after he died, I talked about it often as I struggled to learn everything that had happened. I was trying to process the reality of his death and implied decision he’d made to leave without saying goodbye.

As time goes on, I have actually found his suicide and absence more upsetting rather than less. I have integrated it into my life narrative on an intellectual level, but I still find it impossible overall to reconcile or accept. Therefore it isn’t something I often bring up or discuss anymore with others.

What I do understand is that there are still many others at risk of taking their own lives. Millions of Americans struggle with undiagnosed mental illness and/or lack adequate healthcare.

And I did eventually get to the place where I wanted to do volunteer work in the community on the suicide prevention side. So I felt happy when I received an invitation in June to help decorate the AFSP float for the Capital Pride Parade, and then walk in the parade. The first DC parade was held in 1975 – almost 50 years ago.

Since that time, according to NBC Washington, Capital Pride events have “evolved to uplift people across the spectrums of gender and sexuality – and across abilities, locations, ages and more.” I certainly felt that in the atmosphere last summer when we attended during my mom’s visit.

These days, Capital Pride events draw crowds upwards of a half million people. Next year, organizers expect historic levels of attendees at World Pride as the event marks its 50th anniversary.

Marching in the parade was an unforgettable experience. It took almost 90 minutes in the sweltering direct sun after the parade began for us to also move; several blocks of floats had to go first. But walking down the streets thronged by spectators cheering and reaching out to us made me feel like a celebrity. But it was actually AFSP that was the star.

I threw out AFSP beads and several pounds of Jolly Ranchers I’d lugged to the crowds that lined the sidewalk. But my participation – like that of the other volunteers – went beyond simply caring for community and wanting to be part of an inclusive event: all the AFSP volunteers have been hurt and damaged by suicide loss.

“Know the Signs; Save a Life,” proclaimed one of our placards. The girl carrying it bounced it up and down and spun it around continually. Numerous people yelled “Thank you!” as we marched by. One person called out, “You saved me so many times!” I felt tears burn my eyes and I was glad for my sunglasses. I turned around and threw another fistful of candy over the crowd, seeing several hands fly up to catch it as a shout went up.

Sadly, there is as much of a need than ever to reach out to others about their mental health. Recently The Trevor Project – a national organization providing crisis intervention and suicide prevention services to LGBTQ teens and young adults – released new state-level data on LGBTQ youth mental health, victimization and access to support.

The Trevor Project’s nationwide survey data reported 39% of LGBTQ youth in the United States seriously considered suicide in the past year, including 46% of transgender and nonbinary youth. In some states, like my home state of California, these numbers are even higher.

After reading statistics like that, in addition to those I’ve discussed in the past, is where it falls to the rest of us to get involved. To stop the skyrocketing suicide rates in our country, especially with marginalized youth, we need to both see the signs, and be willing to act. We need to say to others and specifically to those who are suffering: you have a place here. You are not alone. Don’t lose hope. Tomorrow is another chance to start again. Tell me what troubles you, and I will walk with you. Until.

Whether Pride events float your boat or not, I think it’s our broader social responsibility to create safe spaces. To be available to listen, and to care. My friend T was a person like that, who lent a listening ear to others and provided comfort to friends when they were down. He openly supported people who were struggling, but was not always open about his own struggles.

T was not part of the LGBTQ community. Technically, neither am I, aside from being an ally. But in my experience, T did not judge others. He always supported every individual person’s right to make their own decisions. He had a unique way of looking past a person’s outside presentation, religion, taste in music, or background to see the person they were on the inside.

He then took it a step further and extended acceptance to everyone, without question. He did this without boxing people into categories and drawing assumptions about them. This explains why he was able to be friends with people even much different than him. Underpinning his behavior was his attitude that each person should live life on their own terms. These are qualities he improved in me. I felt like he would have understood this event and would have approved of extending a positive message about mental health support to whomever needed to hear it.

I can’t say the things I want to him now, but I can try to move the needle by reaching out to others. And that’s why attending this event was important to me, and why I’d like to do it again next year despite the uncomfortable aspects of participating like heat, waiting around, and insufficient public bathroom access.

From suicide to genocide, the Department’s two-day atrocity prevention course was focused on how U.S. foreign policy assists in anticipating and halting genocide.

We discussed five main tools diplomacy employs around the world in service of this assistance: countering dangerous speech, early warning and response, local dispute resolution, support to peace processes, and transitional justice.

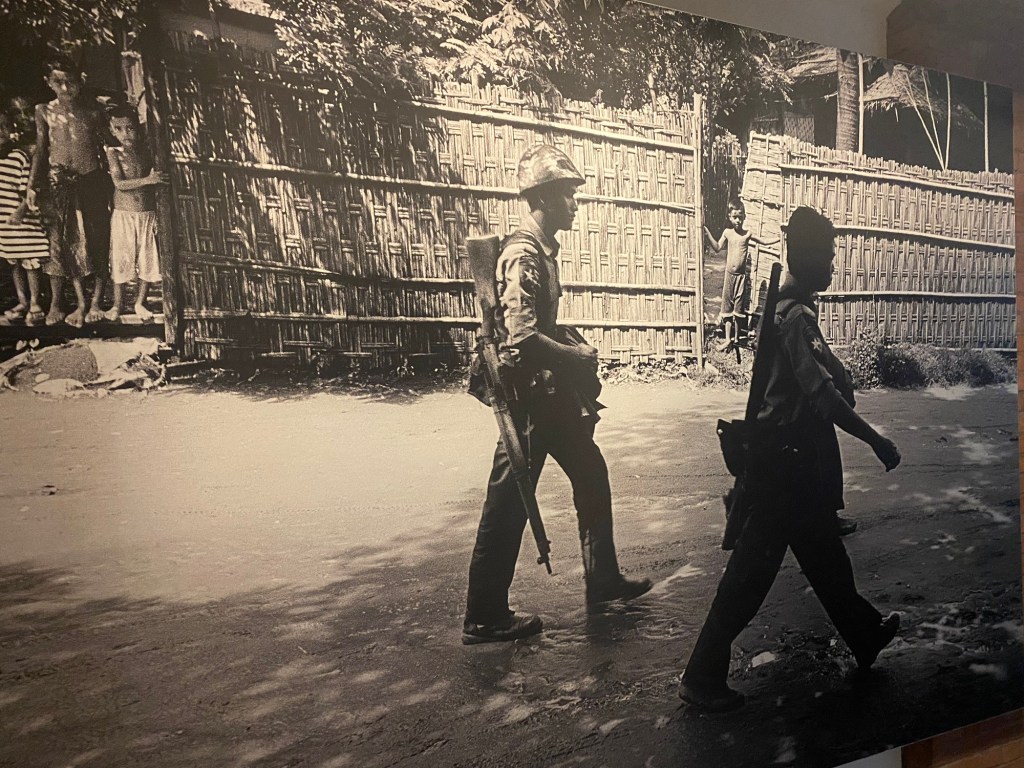

Given that my next post, Rangoon, is currently undergoing a civil war, I thought it was an important class to take. The embassy also specifically recommends incoming officers take it before arriving at post.

So I was very fortunate generally to spend a couple of days at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), which – as a bonus – has a long-term special exhibition on Burma called “Burma’s Path to Genocide.” You can view the exhibition online at the link. If you’re in the DC area, I encourage you to visit the museum and check it out in-person.

If you have an academic interest in this topic, USHMM makes available the 2016 book Fundamentals of Genocide and Mass Atrocity Prevention as a free download on its website. It also posts several online teaching resources and historical information to help the public better understand current conflicts.

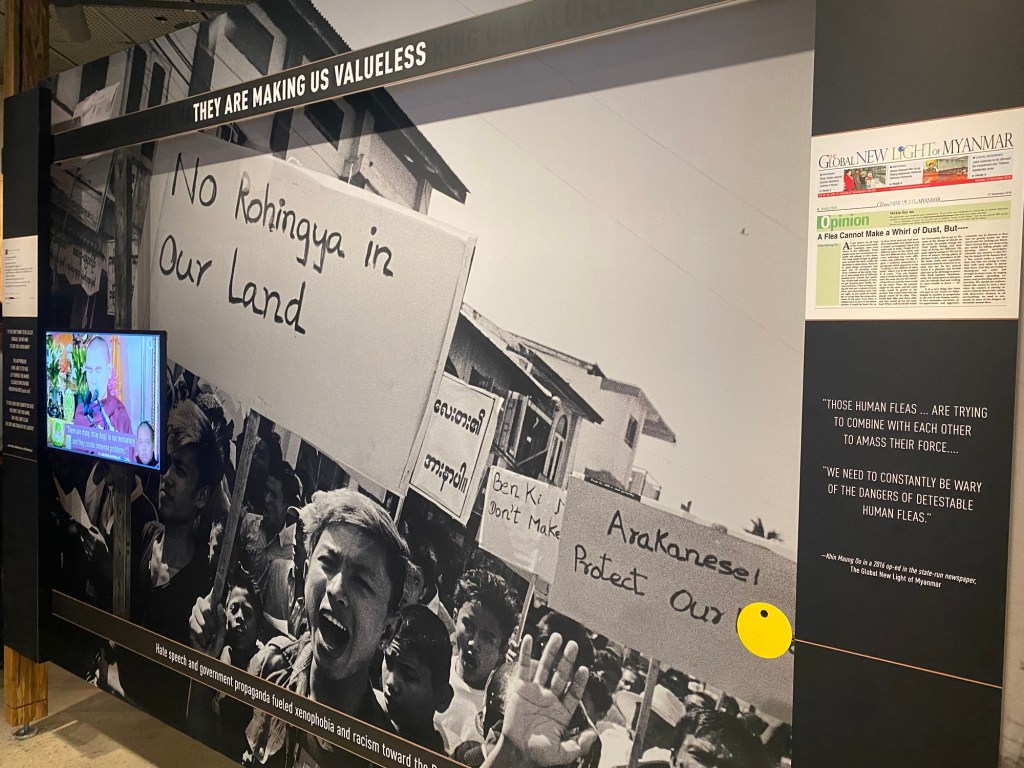

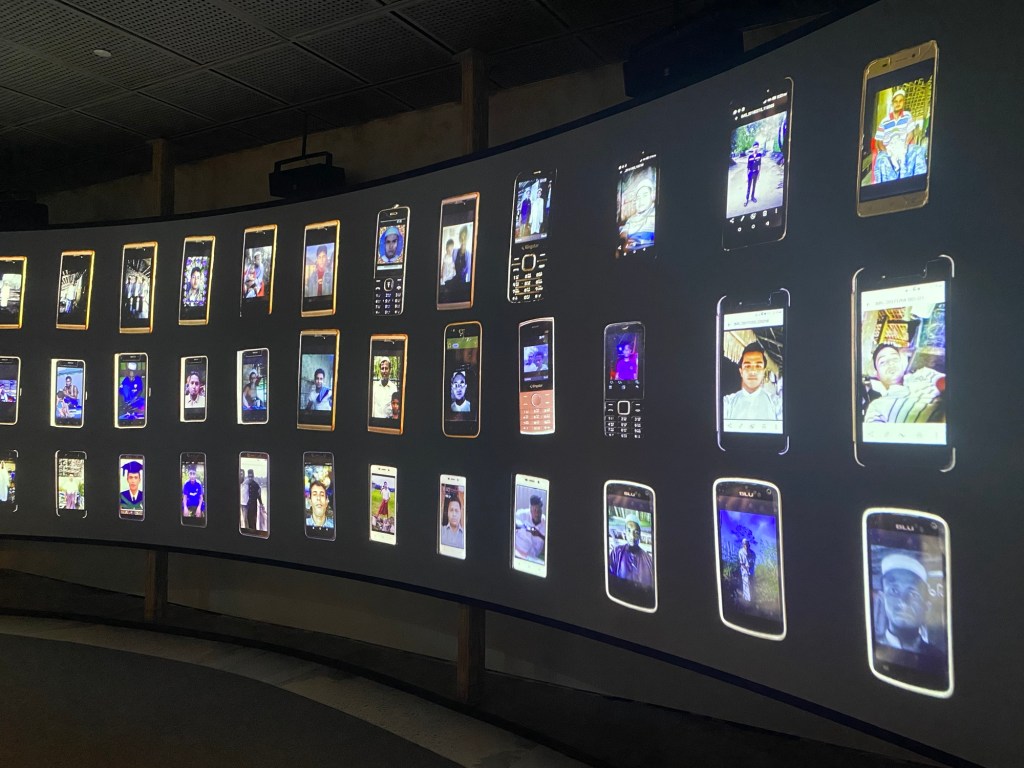

I was unaware until I saw the exhibition the full extent of the way Rohingya people in Burma have been systemically marginalized, stripped of citizenship, and forcibly removed from their homes not just recently, but over several decades. Rohingya people living in Burma predate the establishment of the (current) colonial borders between Burma and Bangladesh, yet, have few rights or legal recourse when displaced from jobs and community.

Of course, I’d heard about the recent plight of over one million Rohingya who have fled into Bangladesh and are now living in overcrowded refugee camps. But I was unaware that inside Burma, Rohingya still have no ability to vote or run for office, their access to healthcare and education is blocked, and they endure restrictions on marriage, childbirth, and freedom of movement. I still don’t totally understand the issue, and have a lot of studying to do on this conflict.

In 2018, USHMM determined that genocide had been committed against the Rohingya. The Department of State followed suit in 2022. There is currently a case pending before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to determine whether Burma violated its obligation to prevent and punish genocide as required by the UN Genocide Convention.

Genocides – like the World War II-era Holocaust the museum is named for – are always foreshadowed. The dehumanization of a single group, hate speech from leaders polarizing societies, removing moderates from public office, labeling civilian opposition views as “the enemy,” and armed conflict are all risk factors for mass atrocities that – somehow – still look clearer in retrospect than they do while they’re occurring.

One of the takeaways of the atrocity prevention course for me was that genocide is always preceded by signs. When the global community is able to see the signs and act multilaterally (including with non-governmental organizations) to address them, there is a better chance of preventing such horrors.

“Atrocity crimes take place on a large scale, and are not spontaneous or isolated events; they are processes, with histories, precursors, and triggering factors which, when combined, enable their commission.”

-former UN Secretary-General BAN Ki-moon, UN Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes: A Tool for Prevention (2014)

It isn’t easy to quantify the costs of suicide and genocide to society. A 2016 Harris Poll survey indicated the vast majority of Americans (94%) believe suicide is preventable, but only 31% responded they were “able to tell” when someone was suicidal. Our atrocity prevention instructor frequently cited a statistic that for every dollar not spent preventing a mass atrocity, it costs $16 to respond later. And we also know that knowledge doesn’t necessarily equal action.

Suicide and genocide are obviously different problems requiring different responses. But what they each have in common is causation by a multitude of factors easier to predict when others know the signs and are able to respond appropriately.

We can’t control other people’s actions, but we can make choices to support people who are struggling. We can also identify the systemic, structural, and operational foundations of atrocities and use a variety of diplomatic tools to dissuade or deter them before they become large-scale crises.

1 comment for “Know the Signs”