When I joined the Foreign Service as a consular officer, future colleagues said to me, “Oh, consular officers have the best stories!”

“Oh yeah?” I smiled.

“Sure. Between the visa fraud, emergency passports, natural disasters, and American citizens getting arrested overseas, there’s no shortage of stories. I once visited this U.S. citizen in jail, you wouldn’t believe what happened with this guy…”

Oh boy, I thought. Tell me. I can’t wait.

Lack of familiarity with consular services could leave you vulnerable at a time when you need help.

The husband of one of my college girlfriends asked me earlier this year if I was an ambassador. I explained to him that I was actually a consular officer, working in one section of the embassy, while ambassadors are in charge of the whole embassy. He looked at me quizzically. “What does a consular officer do?”

You know,” I paused. “Like let’s say, for example, you went down to Mexico on spring break and got thrown in the can. What do you do? You can call the nearest U.S. Embassy or U.S. Consulate and tell them you’re a U.S. citizen who got arrested and you need consular services.”

He laughed. “So you would come get me out of jail?”

“Not exactly,” I said. “But I would make sure you weren’t beat up, help you get access to your medications, if needed, and a lawyer. We’d answer any Congressional inquiries about your case. We would also call your family or a friend to let them know where you were, but only if you asked us to and we had your permission. If you were convicted and sent to prison, we would monitor your sentence and visit you every few months.”

“Whoa,” he said. “No get-out-of-jail free card, huh? I guess people who break the law here get in trouble regardless of citizenship, too.”

“Yes,” I said, “But the United States also has an obligation to inform foreign governments if we arrest one of their citizens. We make the consular notification, and provide access.”’

Then he hesitated. “It’s funny you mention it, because that actually did happen to me in Mexico, a long time ago. In Cancun.” My eyes widened. “But I don’t think anyone was ever notified.”

Even though my friend had been briefly arrested and jailed in Mexico, he wasn’t aware of consular services, and it’s not likely the local authorities notified us. He’d thought he needed to suck it up and pay a bribe.

And I’ve found that to be the case with many Americans. Besides mainstream news stories like the arrest in Russia of basketball star Brittney Griner, or long-term detentions of American arrestees or hostages around the world, most Americans are unfamiliar with what services their government can – and cannot – provide for them outside the United States, and where to go to get those services.

Why do we have consular services?

The 1963 Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (or VCCR) is a multilateral treaty that governs, among other things, consular procedures; the establishment of consulates; the privileges, roles, and immunities of consular officers in the receiving country; and the obligations of the contracting state. The United States ratified it in 1969 after Senate confirmation and acceded to the treaty during the Nixon administration. The notification and access I mentioned above is addressed in Article 36, but you can skim all 79 articles of the treaty in its entirety on the UN website at this link. This agreement is what gives people the right to seek consular services, and consular officers the right to offer them.

Where are consular officers, and what do they do?

As I talked about in my September 2018 blog post “Postcard to Americans Abroad,” consular officers work in embassies and consulates around the world, and in Washington, on a variety of issues involving immigration law, fraud, documenting U.S. citizenship, responding to disasters, and helping Americans overseas with some of their most difficult life moments, including visiting them after an arrest or hospitalization and even repatriating their remains if they die abroad.

Consular Officers provide emergency and non-emergency services to American citizens and protect our borders through the proper adjudication of visas to foreign nationals and passports to American citizens. They adjudicate immigrant and non-immigrant visas, facilitate adoptions, help evacuate Americans, combat fraud, and fight human trafficking. Consular Officers touch people’s lives in important ways, often reassuring families in crisis. They face many situations in their careers as Consular Officers which require quick thinking under stress. They develop and use a wide range of skills, from managing resources and conducting public outreach to assisting Americans in distress.

No, consular officers will not plan your vacation for you, take custody of your minor children, or mediate disputes between you and your AirBnB host. We will help you if someone robs you, if you get in an accident, or if you didn’t realize your passport was expiring and now you’re stuck. If you die on vacation and you’re alone, we might get called in to inventory and pack up your effects. Sadly, I have also been asked to identify deceased Americans, confirm citizenship, and make death notifications. Sometimes this has even involved collaborating with our colleagues at the border to make sure repatriated remains have the right accompanying paperwork for entrance into the United States.

Consular officers try to be good stewards of taxpayer dollars and assist people in our consular districts the best we can with limited resources. It really helps when people do their part, too. I’m limited in how I can help someone if they’re too escalated and verbally abusive to the guards to gain entry to the consular waiting room inside the embassy, even if their situation is legitimately distressing.

We work during the regular business day, and other personnel throughout the embassy (sometime consular and sometimes not) take turns covering the duty after-hours, on holidays, and weekends. One of my former colleagues serving in Turkey wrote a terrific post on her blog about duty calls, which I encourage you to read here.

Travel planning and obtaining consular help

From the International Travel section of the State Department’s website:

The safety and security of U.S. citizens overseas is one of our top priorities. To keep you informed, we provide security updates on travel.state.gov and embassy and consulate websites, and send out Alerts when you enroll in our free Smart Traveler Enrollment Program (STEP).

Planning appropriately to live or travel abroad in terms of abiding by local laws, having adequate medical or evacuation insurance, and registering in STEP so the embassy can text you about changing security circumstances are just a few of the ways U.S. citizens can avoid accessing consular services unless and until they really need them.

It’s really important to review the Learn About Your Destination information on the State Department’s website. There you can learn about unique criteria for entering and traveling in any country you plan to visit. Make a note before you travel of the emergency phone numbers and email addresses for American Citizens Services, and also give them to a non-traveling contact at home. Also note the State Department’s 24/7 emergency line at (888) 407-4747.

It’s a very good idea to check your U.S. passport to make sure it’s more than six months from expiring, consider buying medevac insurance, and download the State Department’s Travelers’ Checklist. It covers topics like customs and import restrictions, travel information for high-risk areas, TSA Pre-check and Global Entry, consent for traveling with minors, driving abroad, evacuation insurance, links to apply for foreign visas and foreign entry/exit requirements, special considerations for female travelers, students, or travelers with disabilities, and much more.

There are certainly plenty of times Americans overseas access non-emergency consular services without something going wrong. Renewing your passport, getting a document notarized, or receiving a Consular Report of Birth Abroad for a child are all routine services and available by appointment. But unfortunately, there are a lot of times where people are down on their luck or victims of circumstances they can’t totally control, and consular officers are there to provide emergency consular services too.

When it all goes wrong…

From losing a passport down a volcano, to one spouse abducting the children from the other and disappearing in a foreign country, to Americans turning up in hospitals naked and beaten with amnesia and no ID, to the wayward traveler who shows up at the embassy at 4:45 p.m. on a Friday with not a centavo on them and nowhere to stay the night – consular officers have seen it all. There are so many people I’ve encountered in consular work whose stories have stuck with me.

I will never forget the American couple who flew to Australia and, exhausted from their flight, rented a car instead of taking a taxi. They promptly drove on the wrong side of the road and died in a head-on accident. The consular officer who made the death notification to their next-of-kin daughter discovered that she was in a Sydney hospital having recently given birth to her first child.

I will also never forget the elderly U.S. citizen who came to Uzbekistan on a Smithsonian tour without medical evacuation insurance and fell at one of the remote sites hours from the embassy, breaking a bone in her neck. The consular officer who went to visit her in the hospital spent hours on the phone with her panicked adult son about the best way to get her to western European medical care.

And I will never forget the men we interviewed in a Mexican border jail about arrests for property damage. One had destroyed half a convenience store with a baseball bat over COVID-related alcohol sale restrictions known as ley seca (dry law). Another had attacked a statue of the Virgin Mary in his neighbor’s yard with a mallet after forgetting to take his psychiatric medication.

I will always remember the man I talked to on the phone as he sat on the airport floor groaning from a gunshot wound to the leg and waiting for his chartered medical flight I was tracking on FlightAware.

I will always remember the homeless former marine who I talked to across the table in a psychiatric hospital, who days later walked with me across the border bridge back into the United States for the first time in almost two years, and into the arms of the El Paso County behavioral health system.

I will always remember the first person I had to call and notify her daughter had died abroad in an accident and the way she didn’t understand, until she did.

I will always remember the woman who called the duty phone from a hotel and said that her boyfriend had been slamming her face into the carpet; when I asked her where he was and if she had called the police, she whispered almost inaudibly, “He’s standing right here.”

I will always remember the family where the mother abducted the son and brought him to the United States, and the father flew from his home country and “snatched” him back before the mom even realized what had happened.

I will always remember the murdered woman whose purse was locked in the safe in my office pending her daughter coming to get it. It had already been two years, and the daughter wanted to wait for police to release the rest of her mother’s property from their custody, including a car and a laptop, so she’d only have to make one trip. The woman’s cane leaned against my safe in the corner because it was too long to fit inside the drawer. Every time I saw the purse in the bottom of the drawer, I felt a pang.

I will always remember the defeated-looking Uzbek man who applied for a visa to go to New York. When I asked him about his purpose of travel, he said he needed to collect the remains of his son who had died unexpectedly the week before. My accidental clumsy Russian in our conversation bothered me all day. I later found his son’s obituary online.

I will never forget the man who scoffed in disgust when I refused his visa application. He bellied up to the window like I was inconsequential and could be bullied. As the only female consular officer in our section, I was used to these slights. “I want to talk to the man,” he sneered, assuming my male colleagues on either side were my supervisors. I replied in Russian, “Sir, I am the man, please exit to the left.” Famously stoic staff behind me somewhere who never laughed at all the ridiculous situations or grammatical errors they heard finally almost choked on it and had to step away.

And I will always remember the lady who had been working without authorization on her prior tourist visa. When I questioned her ability to pay for her next proposed stay in the United States while still adhering to our laws, she shouted at me in Russian something like, “I have money up to my neck!” She flipped a stack of $20 bills up in the air and they rained down all over the floor and counter, some of them getting sucked by the backdraft through my metal deal tray and ending up on my side of the glass. I jumped backwards and held up my arms, calling over my shoulder, “I need a witness!” and all my colleagues stopped what they were doing and stared. “Your visa is refused!” I raised my voice without meaning to as other people helped her pick up the money and she glared at me. All that working under the table money, I thought with frustration. Not what you’d said you were going there to do.

I will always remember the moment one of my first tour officers appeared in my office doorway and said, “That crime victim from this morning made it in with our NGO contact. He’s in the waiting room.” When I asked if the officer had begun the interview yet to determine what help was needed, the officer hesitated. “Well, that’s the thing,” he replied. “He can’t hear or speak, and I don’t know sign language.” I sat for several seconds before replying, “I only know how to spell out the sign language alphabet letter by letter. So let’s get some paper.” The officer wrote notes back and forth and eventually figured out what had happened and got him home.

And I will always remember the woman who appeared in a local shelter, with no luggage, funds, or medication, who was certain she’d been on her way to the airport for a job abroad. There was no job, and her intended destination was a 16-hour flight away. She looked dazed, unfocused, and was wearing little more than a dirty white tank top and slacks. I was shocked when I looked up her prior passport photo. The photo could have been attached to any Washington high-flyer’s biography without anyone batting an eye: pearls, lipstick, suit jacket, confident smile, clear eyes. She’s us, I almost gasped to a female colleague. What happened? my colleague replied, shuddering with dismay. When we reached out to her sibling to see if he could Western Union her money for a return bus ticket, he was not surprised in the least. He said, “Oh no. Not again.”

I will always remember the people who thanked me, and the people I was able to help. We usually don’t know how things end up for them, and some of these cases I wonder about long afterwards.

It’s complicated.

I once brought an American prisoner convicted in Australia of narcotics trafficking a stack of magazines. He’d been in for over a decade and his sentence had a few years to go. He expressed excitement at hearing an American accent for the first time in a year.

After we finished our paperwork and sat for a while, I asked him about the moment it all went wrong. He paused for a moment, and then told me it was when he was standing in a bathroom stall at JFK and had a chance to dump the drugs. “But I didn’t,” he said. “I got on the plane to Sydney. And in that instant, everything changed. It was too late.” His eyes were filled with regret. “I’ve thought of it a million times. But it never changes. And I can’t defend it.”

“You don’t have to,” I said. “I’m not the judge.”

I paused. “What happened to your car, your apartment, all your stuff back in New York?” He just looked at me. “It’s all gone. I don’t even know. I lost everything a long time ago. Someday I’m going to try and put it all back together.”

As I drove the highway back to Canberra, I thought about it. Where does it all go wrong, I wonder? People make mistakes, people are unlucky, people become victims. We are supposed to reserve judgment, but we are also human. Getting woken up in the middle of the night because someone calls the emergency duty line to ask, “I’m thinking about traveling to x and am just wondering what the situation is currently?” I think, Uh, the situation is that this is an emergency line that needs to be kept clear and the information you’re requesting is publicly available online, sooo.

But somehow, the sympathy and human frailty I have always found it easy to connect with and meet on its level comes through. I tell the person calmly and directly what they need to know. I might be the only consular officer they ever meet or talk to, and I know I’m representing an organization rather than myself.

Untreated mental health problems put Americans at risk

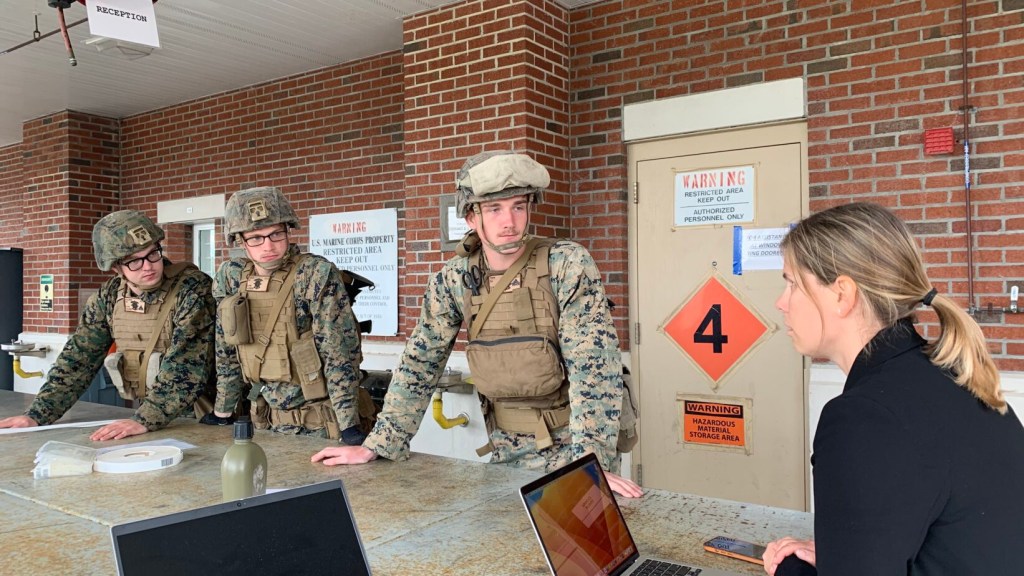

One afternoon in Mexico, I walked outside the consulate to talk to a man the guards wouldn’t let in. He was unshowered, excitable, and making demands – potentially a security risk. I entered what we jokingly called our “shack” and approached the external window. I’d already observed that he’d been repatriated for destitution from half the U.S. embassies in Latin America. I brought a first tour colleague with me to observe.

“Sir,” I said, “My name is x. What’s your name?” He told me. He looked enough like his prior passport photo that I didn’t doubt it. “What seems to be the problem today?”

He initiated a lengthy rant about needing a new passport so he could fly to Bogota. I explained to him that until he paid his indebtedness to the U.S. government for his prior trip home, we wouldn’t be allowed to issue him a new passport. I reminded him how to go about doing this, but he interrupted me. “I have a meeting in Bogota with kings, queens, and princes,” he said, raising his voice and looking panicked. The mouth of the consular officer next to me dropped open for a moment. People standing in line to get into the building peeked around the corner.

“I understand it’s important to you,” I said evenly, “And that’s why you gotta straighten this out.” He nodded and followed my finger as I pointed north. “I’d like you to go back to El Paso, where you can take care of this. It’s better if you’re there than in Juárez, because, you know, this is kind of a dead end for you.”

“Kings, queens, and princes,” he repeated, nodding and backing away. It took a while, but he finally realized Juárez was not going to be his path to Bogota. How did you get him to leave? another officer asked me. I’ve talked to him twice. He’ll be back. But he didn’t come back. I went to my office and wondered what harmful decisions I would make if I weren’t in possession of all my faculties. A lot of them, undoubtedly. I felt sad, but almost immediately we had another emergency with a firearm-related arrest at the border and I put it to the side.

The next time I got called outside to talk to someone the guards wouldn’t let in, it was an elderly gentleman shouting about impending nuclear holocaust and refusing to return to Texas. “The Soviet Union is going to destroy Texas,” he relayed, exasperated at my suggestion he take the green bus to the free bridge. “Texas won’t even be there next week.”

I thought about mentioning that if Texas were a goner, Juárez would be right behind, but I didn’t think that was the right tact. Looking at his age and presentation, I leaned across the counter conspiratorially. “The Soviet Union scrapped those plans 30 years ago,” I said, looking him dead in the eye. “I haven’t even hidden under my desk in years.” A vague look of relief crossed over his face. I continued, “I promise you it’s safer at home in Texas than here in Juárez.” It was the truth without feeding much into his delusion.

It took about 20 minutes of convincing him, but when I laid out the options of walking back across the bridge vs. staying in a Juárez shelter crowded with migrants, he had a moment of lucidity. And thank goodness, because he was a magnet that would have surely attracted misfortune, albeit not of the nuclear kind.

Staying in our lane

Although there is a lot we can do, there are also things we cannot do, or should not do. Unfortunately, I’ve had some U.S. citizens get pretty mad with me over unrealistic expectations of what U.S. government assistance should provide.

One woman calling from the United States was frustrated that I wouldn’t drive to her ex-husband’s house in rural Mexico in my personal vehicle, pick up her infant son, and take him to a doctor’s appointment because she and her ex disagreed about their son’s health.

Another person demanded she be allowed to “move in” to the consular waiting room with several pieces of luggage because the van she’d been living in broke down and she didn’t have money to fix it.

A third person yelled at me for asking him to sign a form indicating he would repay a government loan to buy him a return ticket to the United States; I suppose he thought it was the responsibility of U.S. taxpayers to get him home after he had become destitute in Mexico through choices he alone made.

I’ve had to tell people things they don’t like, like when it sounds as though they’ve fallen for a romance scam because their U.S. citizen fiancé who they’ve only ever met online and sent money to doesn’t actually exist, or that we can’t issue them a passport because they have a child support arrears hold. But I try to do this politely. I’ve gone overseas and done some dumb things myself, but those are stories for another day. The point is, far be it from me to have any judgment for whatever is going on, even when it’s really egregious. I try very hard to maintain a demeanor of respect and in the majority of cases, it is recognized and returned.

Whether it’s helping U.S. citizens, interviewing applicants who’d like to travel or immigrate to the United States, or talking to the public about our work, my future colleagues were right. Consular officers do have the best stories. And I would LOVE to hear more of them, whether from the U.S. citizen or the consular officer perspective. Soon I may know more about my next consular tour, which will give me plenty of more stories to remember.

4 comments for “Consular Officers Have the Best Stories, Part I”